The Campbell Story

Early Life and Education

Jeffrey Worthington Campbell was born in Boston on March 1, 1910. His father, Jeffrey Sr., was Black and made his living, according to the Registry of Births, as a commercial traveler. Jeffrey’s mother, Lillian, was white. Her marriage caused a significant rift in her relationship with much of her family, although she remained close to her mother who lived with them for many years. Jeffrey’s sister, Marguerite, was born in 1916. Jeffrey Sr. was killed in a racially motivated attack when Jeffrey was 12.

The family moved to Nashua around 1919. Young Jeffrey, after doing some “church shopping” with his mother and sister, decided to attend the local Universalist church, the Universalist Church of Nashua. He became an official member of the church when he turned 18.

He was an active participant, and leader, in children and youth programming in the church. He also became involved in the local YMCA and exceled at school both academically and in his extra-curricular activities. At Nashua High School, he was on the editorial staff of the school yearbook, the Tattler, and also participated in a number of theatrical and musical productions. During his high school years, Campbell revealed a dedication for both social and ecological justice that he also pursued throughout his life: Campbell joined a local picket line in support of organizing workers. Campbell also penned a letter to the editor to protest the levelling of a prominent local tree.

After high school, Jeffrey Campbell was accepted to the Theological School at St. Lawrence University in upstate New York. He was the first African-American to enter this school and his presence immediately presented a challenge and a soul-searching within the Universalist denomination. Campbell was an amazing student inside and outside the classroom: in 1934, while serving on the executive committee of the American Student Union, he helped organize the first nation-wide student anti-war demonstration.

Seeking Employment, Finding Opposition

After graduating in 1933 and being ordained as a Universalist minister in 1935, he was unable to find a permanent position. His race overshadowed all other considerations of his resume, despite supportive and glowing recommendations from the people who knew him. In 1938, the Unitarian denomination granted Campbell fellowship on the basis of his Universalist credentials. But this acceptance did not lead to any permanent ministerial positions. Also in that year, Campbell ran for governor of Massachusetts on the Socialist Party ticket. In that race he came in fourth out of eleven candidates.

In 1939, the Reverend Jeffrey Campbell officiated at the wedding of his sister, who had recently graduated from the University of New Hampshire. Marguerite married Francis Davis, a white man who studied theology at St. Lawrence University with her brother. On August 12, 1939, the editor of The Christian Leader, John van Schaik, published an editorial entitled “Idealism and Realism in Mixed Marriages” in which he condemned mixed marriages because of the hardships they cause on the children.

The editorial was a thinly veiled attack on the Davis-Campbell wedding, and more specifically Jeffrey Campbell’s role as officiant of this wedding. Campbell wrote a response to John van Schaik, which The Christian Leader published in February 1940, entitled “Personality, not Pigmentation”. The debate between Campbell and van Schaik prompted many Universalists to write letters to the editor on both sides of the issue.

Careers as Dedicated Universalists and UUs

During the mid 1930s, Jeffrey Campbell supported himself with part-time and temporary leadership positions, in the process becoming a leader in the Universalist Youth ministry. In 1939, Campbell won a fellowship to study theology in England from the peace organization Fellowship of Reconciliation. Shortly after Campbell arrived in England, World War II began. During the war, Campbell declared himself as a conscientious objector, and supported himself after his fellowship expired by teaching returning soldiers and their families. Because travel across the Atlantic was dangerous, he remained in the England for the duration of war. Because of his dedication to his work, he taught in England after the completion of the war.

Marguerite shared her brother’s dedication to peace. In 1940, she penned a letter to the editor in The Nashua Telegraph opposing conscription. She was also dedicated to the Universalist denomination, even though its leadership consistently rejected her and her service because of her race. In a letter to The Christian Leader in 1942, John Murray Atwood, Dean of St. Lawrence University, noted that the newly ordained Rev. Francis Davis, Marguerite’s husband, still had no ministry. Because of Davis’ skills and ability, in addition to the shortage of credentialed Universalist ministers, Atwood concluded that this could only be because of the racism directed at Davis’ wife, Marguerite. Indeed, Davis never found a ministry, and instead became a social worker. In the 1950s, Marguerite began work with the Universalist Christian Association, and continued to serve the denomination after the merger at the newly formed Unitarian Universalist Association. Marguerite only retired from this work in the 1980s.

After his return to the United States in 1951, Jeffrey Campbell took a position teaching English Literature at the Putney School in Vermont. He remained on the faculty there for the rest of his life, while also trying, repeatedly, to gain a full-time position as a UU minister. He never succeeded. He did serve as a part-time minister at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Amherst, Massachusetts and then as on-call minister for the Unitarian Universalist Church of Brattleboro, Vermont, a position for which he was not paid.

In 1969, at the Unitarian Universalist General Assembly at Boston, Reverend Jeffrey Campbell delivered a sermon entitled “A Road for Everyman”. Unfortunately, Campbell’s sermon was overshadowed: that year, members and supporters of the Black Affairs Council walked out of the conference to protest proposed cuts to their funding.

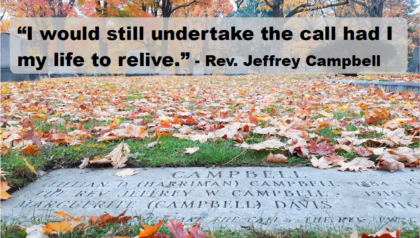

Burial in Nashua NH

The Reverend Jeffrey W Campbell died in Brattleboro, VT in 1984 and is buried in the Edgewood Cemetery in Nashua, together with his mother and his sister, Marguerite. Their graves were unmarked until we installed the marker pictured below.

Looking for more? You can read the article “I Would Still Undertake the Call” from UU World-Winter 2018.